There’s a throughline from attempts to reform the art market in the ’60s to artists like Simon de la Rouviere’s work today.

Screenshot of Simon de la Rouviere’s The Artwork Is Always on Sale V2 (2020).

Amid all the recent backlash against NFTs, the real and exciting possibilities that blockchain technology offers for solving longstanding flaws in the art market could be lost. The great promise of blockchain is something more than just letting people buy and sell digital art. This new technology holds the potential to give artists of all kinds equity in their work.

A smart contract is a code that executes a set of conditions required for a trade to occur; if one condition fails, then so does the trade. Thus, by adopting blockchain smart contracts to trade ownership of their work, an artist can ensure resale royalties as a condition for the transfer of title, meaning they automatically get a cut of any future sales of their work.

Indeed, it’s easily conceivable that with this technology, an artist could stipulate that her sale price compensate not only herself and the gallery, but gallery staff, studio assistants, or a non-profit, any or all of whom might continue to be compensated in future resales. Though such ideas are yet to be codified, the new interest in the technology has already made artist royalties a reality for contemporary creators in a newly tangible way—a dream of five generations of artist-activists who have fought to solve the problem of how to get a bigger share of the art market.

There is some outcry, now, that blockchain represents the final collapse of the art world into a hyper-commercial, speculative market. Yet if that happens, the industry has only itself to blame for ignoring design options within this developing space, as well as for refusing to support any of the many past social or legal proposals to uplift artists.

Early Efforts

As early as 1883, the artist Frank T. Robinson worked with the New England Manufacturers and Mechanics Institute to establish equity payments for artists in group shows, but most attempts to improve the lot of artists date back to the Depression era.

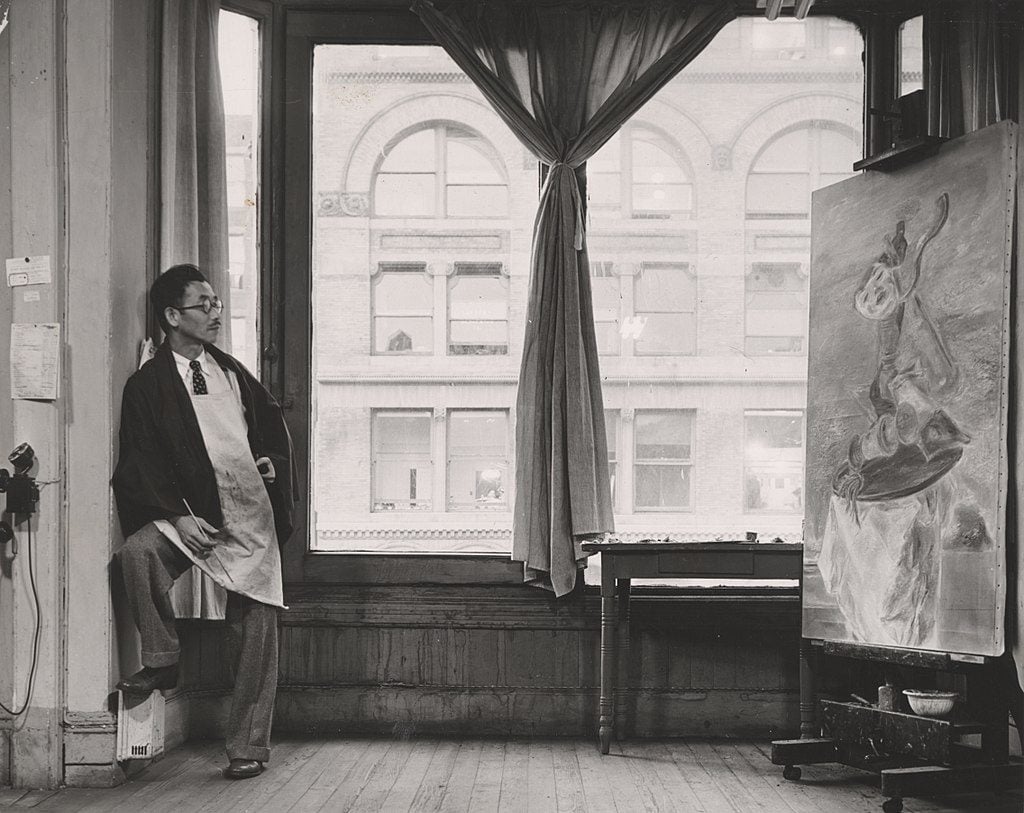

Many artists involved in the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s would go on to found Artists Equity Association in 1947, with the explicit mission “to address business and economic issues affecting American artists.” Yasuo Kuniyoshi, an artist who had produced anti-Axis imagery for the war effort but was nevertheless declared an “enemy alien” in 1941, was the organizing force and first president (1947–51).

Kuniyoshi working on his painting “Upside Down Table and Mask” in his studio near Union Square at 30 East Fourteenth Street in New York City. Photo by Max Yavno, courtesy the Archives of American Art.

Kuniyoshi worked strenuously to avoid political language like the word “union” at a time when the nation already interpreted socialist tendencies among artists as inherently un-American. He gathered an impressive roster of 160 established and emerging artists including Jacob Lawrence, Alice Neel, Louise Nevelson, Isamu Noguchi, David Smith, and Charles Sheeler as founding members. A select group developed the initial 15-point program, which included such wide-ranging concerns as an emergency welfare fund for artists, a group health insurance plan, artists’ rights surrounding televised work, museum board representation, the desire to cultivate state and federal art projects, rental fees for exhibited work, and more.

It was an impressive effort, but even famous members like Grace Hartigan, Frank Stella, and the de Koonings could not leverage their celebrity to get the rights the group sought. Internal disputes eventually led to a split within the AEA. Nevelson served as the last national president from 1963 to 1965. (New York’s Artists Equity Association now carries the mantle, offering workshops and a members’ gallery on the Lower East Side.)

In general, American artists still retain no control over how a work is used and gain no compensation for any increase in its value after it is first sold. France recognized a resale royalty all the way back in 1920, and most of Europe followed—but such measures have been repeatedly rejected within the United States. The Art Proceeds Act proposed in 1966 that artists retain a three percent royalty right on all resales. The same was suggested for the revisions to the Copyright Act of 1976. In neither instance did it succeed.

The Siegelaub-Projansky Agreement

In 1969, the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC) formed after the artist Takis objected to the way his Tele-Sculpture (1960) was displayed at the Museum of Modern Art. Starting from this concern with artists’ lack of legal or political rights regarding exhibition practices, the AWC’s activism in the following years would eventually grow to target museum policies, artists’ financial rights, health insurance, racial equality, and more across several open hearings.

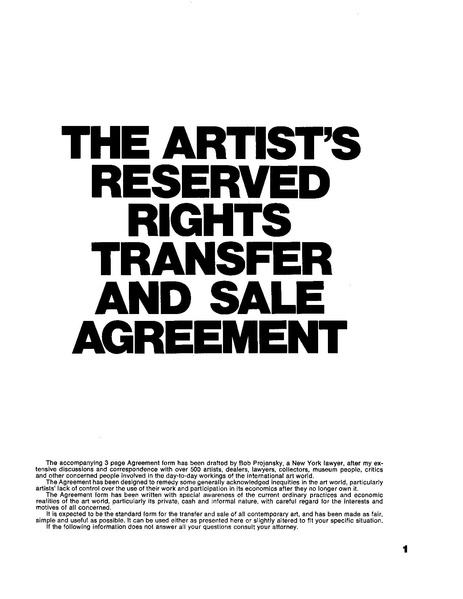

Among those intervening in these debates was the art dealer, collector, and writer Seth Siegelaub. Inspired by the foment around the AWC, he composed the Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement with lawyer Robert M. Projansky. It was an effort to change industry practices through both social pressure and legal means, by setting up a system through which an artist got a cut of secondary market sales going forward.

Charlotte Kent is assistant professor of visual culture in the Department of Art and Design at Montclair State University.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Source: ARTNET NEWS